Massive neutron stars

investigating EOS and magnetic effects

The first neutron star (a pulsar) was discovered accidentally by then graduate student Jocelyn Bell Burnell more than fifty years ago. Ever since, everything we learn about these objects confirms the fact that neutron stars are some of the most extreme objects in our Universe. A typical neutron star contains something like the mass of the sun within just a 10 km radius. At their cores, neutron stars can reach densities several times the nuclear saturation density (the densities within atoms). These stars are probably the only laboratory that we know of at present that exhibit matter existing in such extreme conditions. In fact, the conditions are so extreme within neutron stars that we still do not know the exact equation of state (EOS) that governs these objects. Strong interactions particularly are poorly constrained at these high densities. This is why there is no fixed “Chandrasekhar” type exact limiting mass for neutron stars.

Different high density EOSs have been proposed over the years. A very popular class of phenomenological EOSs are the relativistic mean field models. Dense matter EOSs are constrained in two ways - astrophysically, from neturon star observations; and from laboratory measurements of the properties of nuclear matter at saturation density. Each of these EOSs result in a specific mass-raidus relationship for the neutron star, with each supporting a certain maximum mass. Additionally, at the high densities in neutron star cores, exotic particles, which do not exist in stable form terrestrially, can further be present leading to further complexity.

Massive neutron stars are then of interest in multiple ways. Observationally detecting more massive neutron stars allows us to constrain and rule out more and more of this unknown high density paradigm of nuclear matter. On the other hand, there exists a well known “mass gap” in the literature between ~ 2.5 and 5 solar masses. With gravitational wave observations such as GW190814, this gap is slowly shrinking and it could be that massive neutron stars are what end up populating it. It all then comes back to the question - How heavy can a neutron star get?

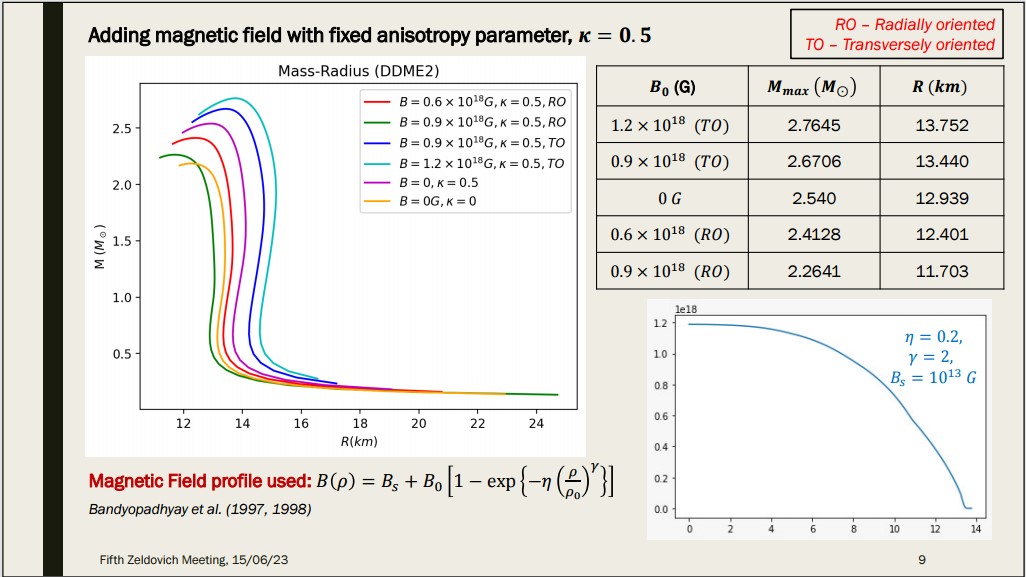

On the other hand, as with any compact star, it is not only the EOS which determines mass but also additional effects that serve to push against gravity. One effect in particular, that serves to be extremely relevant, both observations and in the interest of “massive” neutron stars is the underlying magnetic field. High magnetic fields can have many effects - in fact, a high enough field can lead to microscopic changes in the EOS itself. Magnetic fields can also lead to the star being generally anisotropic and deviating from spherical symmetry.

In this work, we bring all the above considerations together to investigate massive, magnetized neutron stars. We consdier a few phenomenological EOSs, which we felt best fit both the constraints mentioned above. We assume approximate spherical symmetry and introduce an analytical model for both the magnetic field (considered with two different orientations - radial and transverse) and a general model for the anisotropy (adapted from Bowers and Liang). We have also included the exotic hyperon and delta particles in our EOSs considered. It appears that under all these physical effects working together, mass gap type massive neutron stars could very well exist.

This is a brief description of work done in collaboration with Prof. Banibrata Mukhopadhyay of IISc and Prof. Fridolin Weber of San Diego State University. This work has been accepted for publication in Physical Review D. You can find the arXiv preprint here. All plots generated using Python 3.6.9.